Which of these four reasons best describes your own experience or views?

First, you hate being corrected by arbitrary autocrats who would rather feel superior to you than communicate effectively with you.

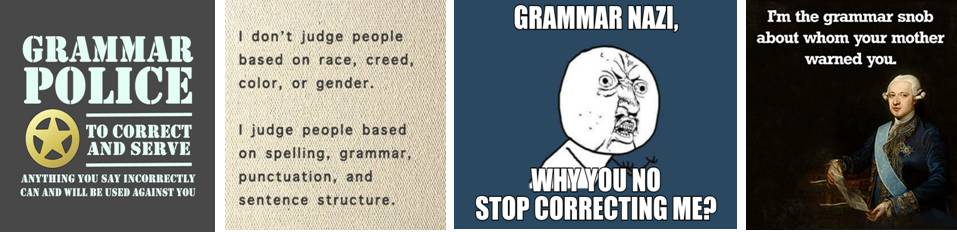

Here are some typically condescending answers to the question “What is good English?” (Do you agree with any of them?)

- It's the “King’s English.” Or the Queen’s. Or what Shakespeare wrote in his sonnets.

- It’s the language spoken by educated persons in Southern England. It’s “proper English,” an upper-crust version of “standard English.”

- It’s what my aristocratic English teacher taught me in the most privileged grammar school in my superior nation.

- It’s academically correct composed prose, based on traditional standards of scholarship from formal schooling.

- It’s the socially acceptable English spoken by members of my political, ethnic, religious, social, or other peer group when we’re together complaining about the world.

Now be honest: Are any of these “definitions” your real reasons for learning or improving your English? Do they help you get ahead in life and work? Does speaking or writing in any of these ways improve your situation or that of your community, environment, country, or world? And if not, why would you want to “aspire” to them? And why would you want anyone else to do so?

Not many “real people with real purposes” strive to learn effective grammar in order to put others down or feel superior. In fact, there are even people that oppose those five paraphrased “definitions of good English.”

For their reasoning, see articles like “My Problem with Grammar Snobs: Grammatical Elitism Helps No One." Its author claims that “socioeconomic classism” based on language use shuts people down. It excludes them from public debate. And it doesn’t help to “take down the grammar snobs” with counterarguments. In fact, pointing out their mistakes makes you sound like an academic purist. It also blocks communication.

But if the question “What is correct English?” means “What is grammatical English?” here’s the most useful, objective answer: it’s “the English produced by its native speakers according to their inherent, subconscious rules. None of those forms of English is more correct than any other. They have all developed during the natural process of language.”

So do you still “hate English grammar” because you feel “put down” or “less than” pedantic speakers or writers? Do their criticisms lessen your self-confidence? If so, here are two common-sense approaches of what to do:

- Whether English is your first or second or a foreign language, do you insist that your way is the only “correct” way to talk or write? Then you need to Quit Being a Grammar Snob. This article gives “Eight Vital Steps” for doing so.

- Decide You Want to Change. • Realize that You can Love English without Being a Snob. • Embrace the Reality of Grammar Evolution. • Accept the Nature of Grammar Rules. • Mistrust Your Childhood Teachers’ “Decrees.” • Be Willing to Learn. • Keep Your Preferences. • Dump Your Rules. • Be Happy.

And if you need even more convincing, get Three (More) Reasons to Stop Being a Grammar Snob.

- For yourself and those you want to help, understand the principles of “Prescriptive vs. Descriptive Grammar.” These distinctions will make a difference in your attitude. Instead of using language structure as a “weapon” to fight or compete with, you’ll grow to appreciate grammatical patterns and rules as practical means to worthwhile ends. Are your aims educational, vocational, practical, and/or personal? Whatever they are, you can and should link “English Grammar” to realistic, useful purposes based on language “notions & functions” or real-life “competencies.”

Second, any statement beginning with “I hate” gets you attention—and maybe even sympathy or comradery. And it may help your psyche.

“Hating” seems to be “in” in many circles. Whatever it means (and it may no longer be a passionate declaration of violent hostility), the word “hate” is fashionable. There are even articles on how hating can be healthy: It makes you feel better. It helps you appreciate your own standards or achievements. It frees you to be honest about your feelings. It protects you against others’ animosity. It validates ideas or people you don’t hate.

In regard to language or content education, there’s a comforting storybook for young immigrants titled I Hate English! And there are visuals saying “Keep Calm and Hate English (Grammar, Class, Teachers, Homework, Study, School, etc.).” Here are some related images:

So do you still “hate English grammar” because it’s fun to complain? Does that outlook limit your ability to improve your life or work? Does it keep you from enjoying language learning? Then here’s what you might want to do:

- Hear a motivational speech or read a blog post that claims you can Transform Your Life by Transforming Your Vocabulary. Its suggestions may “reframe your attitude.” If you “catch yourself in the act,” “play down your negativity,” and “turn up your positivity,” you can “empower” yourself to get what you need through effective use of English grammar. You can “be good and do good.”

- If you truly hate English grammar, don’t study it! Refuse to work at it. Instead, simply play with its forms, patterns, and rules. Use materials that are already “gamified,” such as these three ready-to-use samples. Download them two-sided. Cut them apart. Enjoy—and benefit from—them right away. See how they “feel.”

- Basic Verb Forms Cards, Back-to-Back = 18 Base Forms with Definitions + 18 Past Forms with Illustrated Examples, with 12 Activity & Idea Book pages (Instructions for Use of Materials + 5 Games). “Pick up” verb forms and uses by picking up cards.

- Transitive Verbs with Noun Objects Domino Cards, Back-to-Back = 27 Transitive Verbs + Objects Two-Part Domino Cards, with 4 Activity & Idea Book pages (Instructions for Use with Examples). Acquire verb phrasing naturally while playing Dominoes.

- Kinds of Nouns: Countable (Singular & Plural) Vs. Uncountable in 4 Categories of Meaning: Abstraction, Everyday Objects, Edibles, People or Animals. Differentiate and use nouns of 3 grammatical types with classic, competitive card play.

A third reason to “hate English grammar” is that its structure is “not normal.” Its patterns seem contradictory, illogical, and inconsistent.

With its long history and worldwide use, English has many confusing factors. Here are some of the jokes linguists, teachers, and students like making about it:

Ever ask yourself “Why Is English So Hard to Learn?” Here are some linguistic reasons that language specialists, academics, psychologists, and researchers give:

- Vocabulary: There are up to 2 million “officially recognized” words in the language. Some of those added every year are so obscure that they’re useless to practical speakers.

- Other vocabulary has “restrictive characteristics” that require grammar knowledge to use correctly. Some of the items that “follow specific rules” are compounds, homophones, homographs, phrasal verbs, and Idioms. And surprisingly, the components of such words and phrases don’t always give clues to their meanings.

- Most usable items have “synonyms” (words with the same, similar, or related meanings). Even so, you can’t simply exchange one such “combination of sounds” for “its equivalent.” You have to know the guidelines of “acceptable phrasing.”

- Grammar: Verb tense (+ aspect) management is complicated. There are at least five ways to express “the future.” Past and present forms have various implications, too. “Grammatical markers” like be, do, and have are “confusingly multi-functional.” And “simple little words” like a, an, and the also come with a long list of rules to observe. In addition, sentence + phrase word order can make a big—or a subtle—difference in meaning.

- Pronunciation and Writing: And of course, there’s the ever-frustrating area of trying to read printed words aloud—and, conversely, to write words according to their sounds. Yes, there’s a “basic system” of phonics & spelling to rely on. Even so, there are alternative ways to spell many sounds and other ways to pronounce many (combinations of) letters. And there are often exceptions to these possibilities.

Yes, these potential challenges—and others based on the history and dialects of English—do exist! And if you’re an avid “puzzle solver,” you may even enjoy tackling the anomolies of this particular peculiar language! But to “attain English” effectively and efficiently for real reasons, you’ll want more practical methods for dealing with its difficulties. What to do? Here are two possibilities:

- Is it understanding oral or written English grammar that causes the problem? Then in your own mind, simplify what you hear or see until it makes sense. (Imagine you’re communicating with a five-year-old or a novice English learner.) Listen or read for basic ideas only. Repeat or paraphrase those to yourself without non-essential extras. Locate verbs first—and then their subjects and/or objects. And don’t attend to single words unless they’re strongly emphasized. Instead, receive comprehensible English in meaningful chunks (phrases).

Remember: the brain prefers the shortest encoding of data. It then builds on what it comprehends. It takes in more info without stress or strain. Eventually, it acquires patterns and rules naturally. And what’s unnecessarily complicated, illogical, or senseless may not be worth the effort.

- Or is it producing meaningful English that’s most difficult? In regard to grammar and phrasing, here are some tips to begin with. They’re from Paraphrasing Language, A Resource for Language Teachers & Materials Writers:

- Use short sentences with basic patterns (like Subject-Verb-Object) instead of long ones with modifiers. • If they help clarify meaning, don’t avoid “sentence fragments,.” especially as answers to questions. • Use mostly one-clause simple sentences.

Finally, conventional English teaching and study can be a “turn-off.”

There are many articles like Why Do Students Hate Learning English?. To sum them up, here’s what “suffering consumers of language education” might have to say about conventional English teaching and learning:

- It’s “forced labor.” Even if I want to know English for some reason, required courses, assignments, and grades take away my will to study. They limit my freedom. They slow down my thought and my creativity.

- Other people, especially authoritarian teachers or officials, decide what we have to struggle to learn. Their curriculum and its goals may have little to do with what’s good for us in our lives and work.

- We waste energy hearing or reading about what interests people in other life situations. These articles, literature, or stories may or may not engage us. Often, they use up the time and energy we need to “get on with our lives and work.”

- Most of the time, we don’t get to learn how to use the language in real life. When we do focus on language, we memorize irrelevant rules that don’t apply to everyday communication. Then we “learn” the exceptions—for no apparent purpose at all.

- We repeat meaningless sentences. Or we “diagram” (analyze) them. Or we do boring exercises. And then there’s the torture of mechanical homework. None of these help us to understand or use real English ourselves.

- As long as I can make myself understood in English, why do I need to “study” it? And why would I care to understand anyone who has no other means of communication but this bizarre language?

Are you still “put off” by traditional teaching or study methods? What to do, what to do? Here are two alternatives:

- Use your own methods for acquiring the grammar: these might be imitation, discovering patterns that work for you, using “the natural approach,” enjoying entertaining English, listening and reading a lot. or any means other than those you hate. There are several good websites that give excellent suggestions. These are summarized in the article How to Really Learn English. But no matter what (combination of) techniques you choose, keep your intents and purposes in mind.

- Want to benefit from traditional—or modernized—texts and materials to improve your English? Then make sure that productive examples of its major “teaching points” are contextualized. Check that targeted grammar patterns, structures, and vocabulary appear in simulated real-life situations like those in which you might actually use that language.

The listings in the Competency Charts of the ETC Program (Work/Life English) contain many, many phrases describing what you can do with effective grammatical English. Here are very, very few of them: • Spell aloud. • Name and Describe Things. • Tell What You Need or Want • Ask or Give Directions • Read Everyday Signs. • Make Appointments. • Do Math • Compare Measurements • Identify People

In addition to developing your abilities to understand, speak, read, and write English with “competency-based approaches,” you’ll acquire the language “notions and functions” you need to succeed with English in your life and work. And as these attach themselves naturally to specific grammatical patterns and common phrasing, the “Four Reasons Why You Might Hate English Grammar” will fade happily into the irrelevant.

Here are some of the products built around that concept:

For monthly email newsletters with free tips, tools, and resources for English language learners and teachers, sign up here!

About Work/Life English

Work/Life English is an experienced provider of fun, effective English language improvement content that advances the lives of native English and English as a Second Language (ESL) speakers by improving their English competence, comprehension, and communication skills. For more information, visit: www.worklifeenglish.com.